|

I

|

INTRODUCTION

|

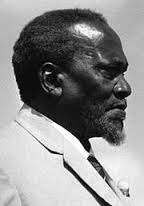

.jpg) Jomo

Kenyatta (1894?-1978), first prime minister (1963-1964) and then

first president (1964-1978) of Kenya. Kenyatta was Kenya’s founding father, a

conservative nationalist who led the East African nation to independence from

Britain in 1963.

Jomo

Kenyatta (1894?-1978), first prime minister (1963-1964) and then

first president (1964-1978) of Kenya. Kenyatta was Kenya’s founding father, a

conservative nationalist who led the East African nation to independence from

Britain in 1963.|

II

|

EARLY YEARS

|

Kenyatta was born in Gatundu

in the part of British East Africa that is now Kenya; the year of his birth is

uncertain, but mos

t scholars agree he was born in the 1890s. He was born into the Kikuyu ethnic group, Kenya’s largest. Named Kamau wa Ngengi at birth, he later adopted the surname Kenyatta (from the Kikuyu word for a type of beaded belt he wore) and then the first name Jomo. Kenyatta was educated by Presbyterian missionaries and by 1921 had moved to the city of Nairobi. There he became involved in early African protest movements, joining the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA) in 1924. He quickly emerged as a leader within the KCA, and in 1928 he became editor of the movement’s newspaper. In 1929 and 1931 Kenyatta visited England to present KCA demands for the return of African land lost to European settlers and for increased political and economic opportunity for Africans in Kenya, which had become a colony within British East Africa in 1920. Kenyatta had little success, however.

Kenyatta remained in Europe

for almost 15 years, during which he attended various schools and universities,

traveled extensively, and published numerous articles and pamphlets on Kenya

and the plight of Kenyans under colonial rule. While attending the London

School of Economics, Kenyatta studied under noted British anthropologist

Bronislaw Malinowski and published his seminal work, Facing Mount Kenya (1938).

In this book, Kenyatta described traditional Kikuyu society as well-ordered and

harmonious and criticized the disruptive changes brought by colonialism. Facing

Mount Kenya was well received in Great Britain as a defense of African

culture, and it established Kenyatta’s credentials as spokesperson for his

people.

Kenyatta remained in Europe

for almost 15 years, during which he attended various schools and universities,

traveled extensively, and published numerous articles and pamphlets on Kenya

and the plight of Kenyans under colonial rule. While attending the London

School of Economics, Kenyatta studied under noted British anthropologist

Bronislaw Malinowski and published his seminal work, Facing Mount Kenya (1938).

In this book, Kenyatta described traditional Kikuyu society as well-ordered and

harmonious and criticized the disruptive changes brought by colonialism. Facing

Mount Kenya was well received in Great Britain as a defense of African

culture, and it established Kenyatta’s credentials as spokesperson for his

people.|

III

|

RISE TO POWER

|

Following World War II

(1939-1945), Kenyatta became an outspoken nationalist, demanding Kenyan

self-government and independence from Great Britain. Together with other

prominent African nationalist figures, such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Kenyatta

helped organize the fifth Pan-African Congress in Great Britain in 1945. The

congress, modeled after the four congresses organized by black American

intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois between 1919 and 1927 and attended by black

leaders and intellectuals from around the world, affirmed the goals of African

nationalism and unity. In September 1946 Kenyatta returned to Kenya, and in

June 1947 he became president of the first colony-wide African political

organization, the Kenya African Union (KAU), which had been formed more than

two years earlier. Recruiting both Kikuyu and non-Kikuyu support, Kenyatta

devoted considerable energy to KAU’s efforts to win self-government under

African leadership. KAU was unsuccessful, however, and African resistance to

colonial policies and the supremacy of European settlers in Kenya took on a

more militant tone. In 1952 an extremist Kikuyu guerrilla movement called Mau

Mau began advocating violence against the colonial government and white

settlers(see Mau Mau rebellion). Never a radical, Kenyatta did not

advocate violence to achieve African political goals. Nevertheless, the

colonial authorities arrested him and five other KAU leaders in October 1952

for allegedly managing Mau Mau. The six leaders were tried and, in April 1953,

convicted.

Kenyatta spent almost

nine years in jail and detention. By the time he was freed in August 1961,

Kenya was moving towards self-government under African leadership, and Kenyatta

had been embraced as the colony’s most important independence leader. Shortly

after his release, Kenyatta assumed the leadership of the Kenya African

National Union (KANU), a party founded in 1960 and supported by the Kikuyu and

Luo. He led the party to victory in the pre-independence elections of May 1963

and was named prime minister of Kenya in June. Kenyatta led Kenya to formal

independence in December of that year. Kenya was established as a republic in

December 1964, and Kenyatta was elected Kenya’s first president the same month.

|

IV

|

PRESIDENCY

|

As president, Kenyatta,

known affectionately to Kenyans as mzee (Swahili for “old man”), strove

to unify the new nation of Kenya. He worked to establish harmonious race

relations, safeguarding whites’ property rights and appealing to both whites

and the African majority to forget past injustices. Kenyatta adopted the slogan

“Harambee” (Swahili for “let’s all pull together”), asking whites and

Africans to work together for the development of Kenya. He promoted capitalist

economic policies, encouraged foreign investment in Kenya, and adopted a

pro-Western foreign policy. Such policies were unpopular with radicals within

KANU, who advocated socialism for Kenya. However, Kenyatta isolated this

element of KANU, forcing radical vice president Oginga Odinga and his

supporters out of the party in 1966. Odinga formed the rival Kenya People’s

Union (KPU), which drew much support from Odinga’s ethnic group, the Luo.

Kenyatta used his extensive presidential powers and control of the media to

counter the challenge to his leadership and appealed for Kikuyu ethnic

solidarity. The 1969 assassination of cabinet minister Tom Mboya—a Luo ally of

Kenyatta’s—by a Kikuyu led to months of tension and violence between the Luo

and the Kikuyu. Kenyatta banned Odinga’s party, detained its leaders, and

called elections in which only KANU was allowed to participate. For the

remainder of his presidency, Kenya was effectively a one-party state, and

Kenyatta made use of detention, appeals to ethnic loyalties, and careful

appointment of government jobs to maintain his commanding position in Kenya’s

political system. Kenyatta was reelected president in 1969 and 1974, unopposed

each time. Until the mid-1970s Kenya maintained a high economic growth rate

under Kenyatta’s leadership, due to a favorable international market for

Kenya’s main exports and external economic assistance.

As president, Kenyatta,

known affectionately to Kenyans as mzee (Swahili for “old man”), strove

to unify the new nation of Kenya. He worked to establish harmonious race

relations, safeguarding whites’ property rights and appealing to both whites

and the African majority to forget past injustices. Kenyatta adopted the slogan

“Harambee” (Swahili for “let’s all pull together”), asking whites and

Africans to work together for the development of Kenya. He promoted capitalist

economic policies, encouraged foreign investment in Kenya, and adopted a

pro-Western foreign policy. Such policies were unpopular with radicals within

KANU, who advocated socialism for Kenya. However, Kenyatta isolated this

element of KANU, forcing radical vice president Oginga Odinga and his

supporters out of the party in 1966. Odinga formed the rival Kenya People’s

Union (KPU), which drew much support from Odinga’s ethnic group, the Luo.

Kenyatta used his extensive presidential powers and control of the media to

counter the challenge to his leadership and appealed for Kikuyu ethnic

solidarity. The 1969 assassination of cabinet minister Tom Mboya—a Luo ally of

Kenyatta’s—by a Kikuyu led to months of tension and violence between the Luo

and the Kikuyu. Kenyatta banned Odinga’s party, detained its leaders, and

called elections in which only KANU was allowed to participate. For the

remainder of his presidency, Kenya was effectively a one-party state, and

Kenyatta made use of detention, appeals to ethnic loyalties, and careful

appointment of government jobs to maintain his commanding position in Kenya’s

political system. Kenyatta was reelected president in 1969 and 1974, unopposed

each time. Until the mid-1970s Kenya maintained a high economic growth rate

under Kenyatta’s leadership, due to a favorable international market for

Kenya’s main exports and external economic assistance.

After 1970 Kenyatta’s

advancing age kept him from the day-to-day management of government affairs. He

intervened only when necessary to settle disputed issues. Critics maintained

that Kenyatta’s relative isolation resulted in increasing domination of Kenya’s

affairs by well-connected Kikuyu who acquired great wealth as a result. Despite

such criticism, however, no serious challenge to Kenyatta’s leadership emerged.

Kenyatta died in office in 1978 and was succeeded by Kenyan vice president

Daniel arap Moi. Moi pledged to continue Kenyatta’s work, labeling his own

program Nyayo (Swahili for “footsteps”). Kenyatta was revered after his

death as the father of modern Kenya. His published works include Suffering

Without Bitterness (1968), a collection of reminiscences and speeches.

No comments:

Post a Comment